What Is a Scrambler Motorcycle? The Reisenduro Renaissance & Legacy of Off-Road Classics Part 2— Janus Motorcycles

March 23, 2024

Share this post

What Is a Scrambler Motorcycle?

And Why the Reisenduro Renaissance Matters

This is the second of a two-part discussion of the history of the off-road motorcycles, the scrambler, and Janus’ latest model, the Gryffin 450. To catch up on part one, click here!

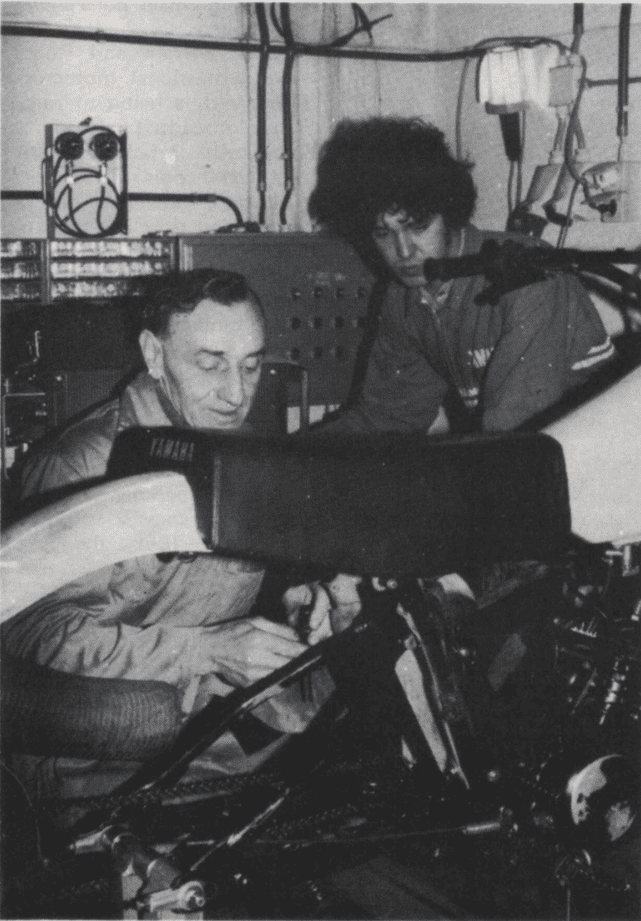

Lucien Tilkens with an early Yamaha YZ using his rear suspension design

A Motorcycle Legacy of Adventure

Starting in the late 60’s Belgian engineering teacher, Lucien Tilkens, began experimenting with a new rear suspension design capable of handling the high power of a CZ400 belonging to a friend of his son. His solution was to triangulate the rear swing arm and connect it straight to the steering head with a long gas shock borrowed from a Citroën car. What he came up with was not only a more rigid chassis design (much like that of the earlier Vincent), but would prove to be far more significant: the accidental benefit of drastically increased suspension travel. At this time, the conventional paired rear shocks on racing motocross bikes had a maximum travel of around four inches. Tilkens’ design, however, allowed for almost double that travel with the possibility of even more. For a more detailed history of rear suspension and Tilkens’ development of the early monoshock rear suspension, see part two of our post on the Halcyon 450 rear suspension.

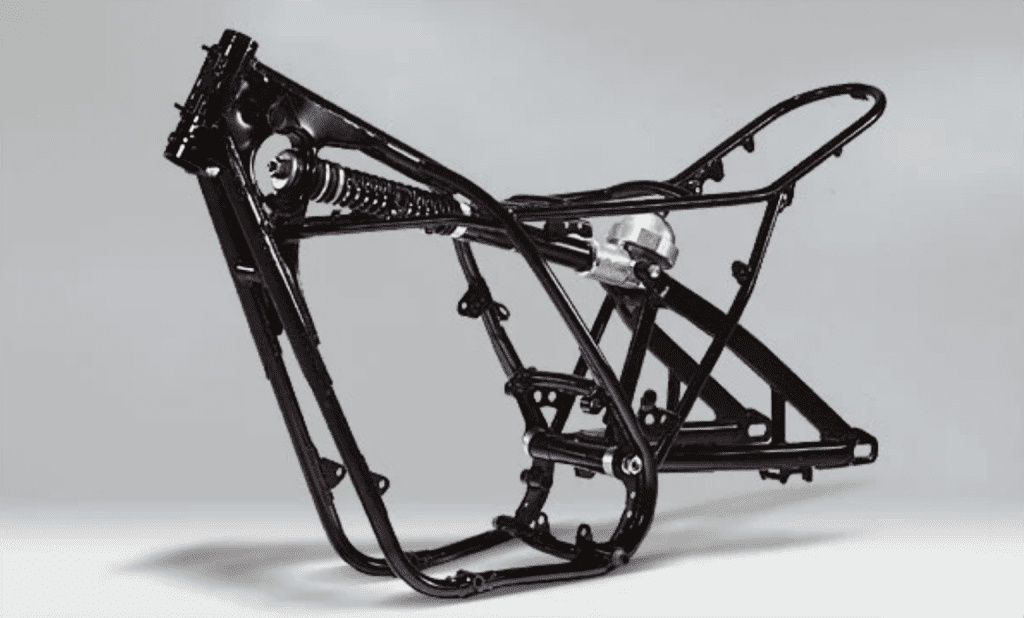

The production Yamaha YZ250B frame and rear swing arm

Yamaha eventually purchased the rights to Tilken’s design and used it on their YZ250B in the 1973 season, famously winning the 250cc Motocross World Championship. What took everyone, including the riders and designers, time to figure out was that it was not merely the increased stiffness of the frame, but the long travel suspension that allowed the bike to go faster in the demanding motocross terrain. The performance improvement was so dramatic that within a matter of months, every major motocross maker was frantically working to figure out how to increase rear suspension travel and stay competitive. In 1975 Yamaha launched the YZ250, the first production motocross bike with a monoshock suspension. Over the next 5 years, all major manufacturers had shifted to variations of the monoshock design and suspension travel had increased to almost a foot on highly specialized machines designed only for motocross racing.

The 1983 SWM Jumbo 350 trials bike

At the same time, the various other kinds of off-road motorcycles started to become more and more purpose-built for their respective types of riding and competition. Perhaps the most extreme example being trials bikes that were paired down to literally nothing more than a lightweight engine, two wheels, and a handlebar. No need for a seat, lighting, or anything else! So too, street machines of the era began to focus on improved handling, power, speed, and comfort for the particular requirements of modern street and highway riding. The 1950’s and 60’s saw the birth of the cafe racer movement, a ground-up push to transform standard models into something more like the purpose-built road racers of the era. By the 1970’s the first production 750cc models (setting aside traditionally larger displacement marques like Harley-Davidson) started to become available. Improvements in metallurgy, suspension technology, tire compounds, aerodynamics; overwhelming competition from the Japanese “Big Four”; and even more significantly, the expansion of the modern highway, continued to push the power and speed of the typical production motorcycle well north of the once mythical 100 mph “ton”. These changing priorities and improvements were often made at the expense of weight, complexity, and more general, multi-purpose rambling.

From Dirt Races to Dual-Purpose Machines

The industry began to settle into distinct design and engineering parameters that favored the increasingly narrowly defined use cases of street or off-road use, to say nothing of the different sub-categories we have mentioned. The gap began to grow between increasingly large and fast road-going machines and smaller and more agile off-road bikes. For example, there really were no motorcycles available at the time that could comfortably accommodate modern highway riding while at the same time allowing for adventurous travel down gravel roads, up mountain trails, or indeed anything without pavement. To allow for this breadth of use, riders resorted to stripping down or otherwise modifying their machines which in turn limited their road-going capabilities.

The BMW R90s

“Gelände/Straße”

By the mid-to-late 1970’s German manufacturer BMW had a problem. Their offerings, while tried-and-true and with a reputation for reliable quality, were beginning to suffer from a lack of development. Meanwhile, the Japanese brands brought an overwhelming new pace and excitement to the market with a multitude of models aimed at all categories and niches of motorcycling. Their rapid development and ability to specialize meant a seemingly constant roll-out of new products at unbeatable prices, both for on-road and off-road use. Attempts had been made by BMW Motorrad in earlier decades to break into the off-road segment, however, pushed by market demand, overall focus had shifted towards high-speed road use. BMW’s conservative model approach and reliance on their air-cooled boxer engine left them increasingly out of touch with the market with falling sales figures.

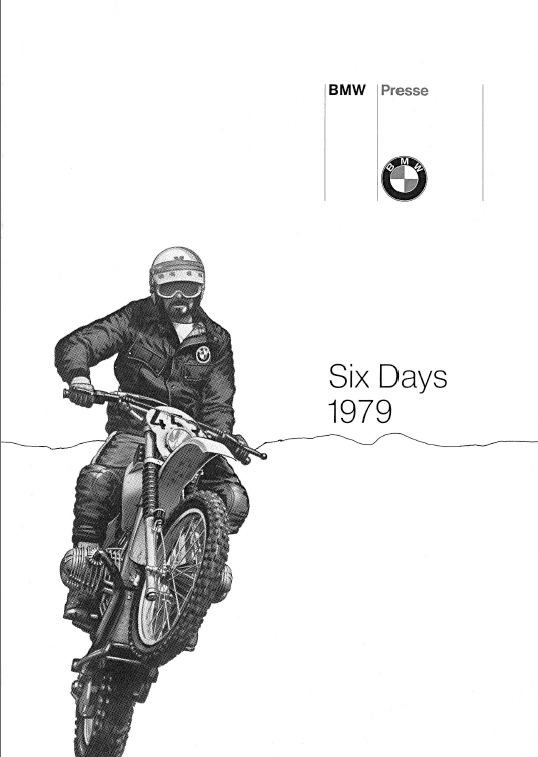

1979 BMW ISDT press pack cover

Around this time, Laszlo Peres, a BMW test engineer and avid off-road rider began tinkering with his BMW’s to make them better able to perform off-road. Then, in 1978, German motor sport authorities introduced a new off-road class that would allow for engines with a capacity over 750cc to compete. Peres, along with two other BMW employees, working without an official development order, decided to build an off-road competition entry. The result was an 800cc boxer engined enduro weighing just 273 pounds. Peres went on to ride the prototype to the runner-up spot in the 1978 German championship and caught the attention of press as well as BMW leadership. With this success the brand continued development and went on the following year to win the championship title as well as a number of medals at that year’s ISDT.

The 1979 works BMW team for the FIM World Enduro Championship. (Left to Right) Rolf Witthöft, Laszlo Peres, Dietmar Beinhauer, Kurt Fischer, Herbert Schek, Richard Schalber

The Rise of Dual-Sport and Adventure Bikes

Still the 800cc boxer was no competition for a lightweight single when it came to technical off-road riding. Although the big boxer was campaigned in trials riding on a limited basis, it was simply too big for ideal use. However, with the revolutionary new K-series platform still several years down-the-road, new BMW management jumped at the opportunity to use their existing boxer engine and tubular chassis in a new way that could drum up excitement and sales. This decision would prove to be one of the best decisions ever made by BMW Motorrad. What they had stumbled on was the missing link in motorcycling left by the industry’s focus on specialization. BMW unveiled the new G/S 80 model at the IFMA show in Cologne in September 1980. The G/S in this designation stands for “Gelände/Straße” or country/road, perhaps more familiar to the English-speaking rider as “dual-sport.” Although the production model would be watered down a bit from the degree of off-road focus for enduro racing, the larger engine provided ample power for thrilling highway touring with luggage, while the off-road capabilities demonstrated in actual competition gave the bike a unique new ability off the main road. This new model would give birth to a new category of “reisenduro” motorcycles that would go on to dominate both on and off-road.

In 1987, with the launch of the GS100, with the “S” in GS now standing for “sport”, the line (apart from the exception of the single cylinder “F”-series GS models) has continued to evolve into larger and heavier ADV bikes now at the 1,250cc mark. While it could be argued that these big ADV bikes are more at home on the highway than the single track, the GS still represents the benchmark for an entire category of riding that has breathed new life into the industry. In the years following the launch of the GS, most manufacturers got into the game with dual-sport or adventure lines from Triumph to Ducati and Honda to Moto Guzzi.

What Reisenduro Means

Reisenduro is another wonderful portmanteau combining the German “reise” for journey or travel with the romance language “duro” with its implications of tenacious endurance.

The author’s 1986 KLR650 (chassis #279) in its natural habitat

No story on the history of dual-sport motorcycles would be complete, however, without mention of that Jack-of-all-trades and master-of-none, the venerable Kawasaki KLR650. Where it could be argued that BMW stumbled into the dual-sport adventure category almost by mistake and from the heavier, road-going end of the spectrum, Kawasaki approached the problem very intentionally. Keeping in mind that the Japanese had dominated the 1970s with purpose-built machines in just about every category of riding, the origins of the KLR650 derive more from the off-road segment. The KLR began life in 1984 in 600cc form, but was revamped for its 1987 debut with an additional 50cc’s, electric start, liquid-cooling, and a total weight of 430 pounds. No dirt bike by any means, Kawasaki marketed the KLR as a “triple-sport” model capable of dirt, street, and highway use. Although this was mostly marketing hype, it is undeniable that the KLR was a machine capable of carrying a rider from gravel road to highway either on the way to and from work or while circumscribing the globe.

Why This Matters for Today’s Riders

Today’s adventure and scrambler-inspired motorcycles owe their lineage to these early Reisenduro machines. Where classic scramblers began as modified road bikes built for muddy trials and cross-terrain fun, reisenduro grew into purpose-built dual-sport and adventure machines capable of real utility for modern riders — whether on a weekend trail or a multi-day touring route.

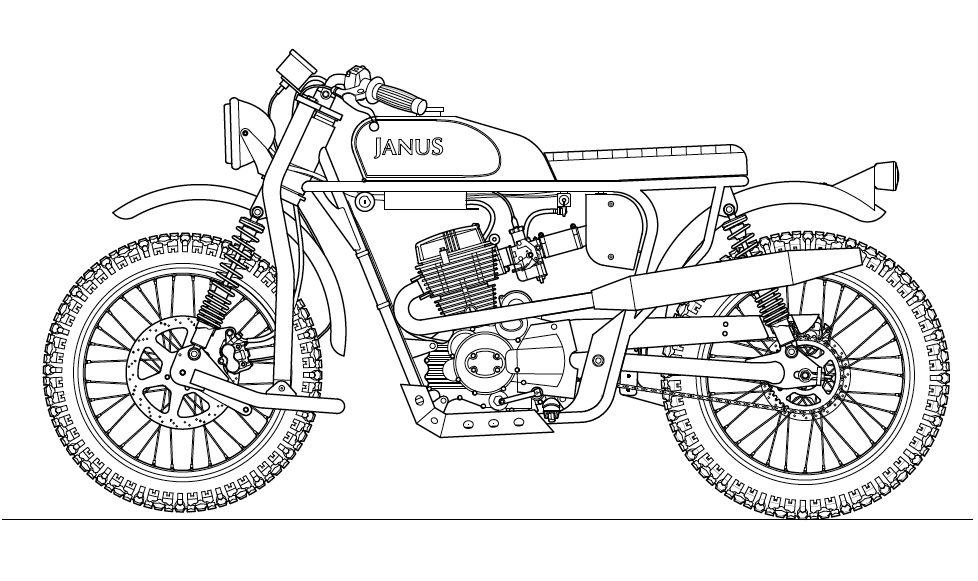

Modern machines that draw from this heritage — including Janus’s own Gryffin 450 — connect us to that spirit of exploration, blending simplicity, versatility, and rugged character.

Janus Motorcycles and the Gryffin 450 — A Modern Interpretation

Whether we call this return to more well-rounded motorcycles a renaissance or a new category, the KLR with its big 650cc carbureted single-cylinder engine, wide aftermarket parts availability, and do-it-all credentials has become an icon for those motorcyclists who, as Arden Kysely, writing for Rider Magazine in 1989 said, “want to enjoy the country they’re riding through, not just blast through to check another route off the list”. In this sense then, we can recognize a motorcycle that returns motorcycling back to something that it had lost in its quest for specialization. My own love for the KLR650, of which I have owned two, has been a major influence on our philosophy at Janus and has carried through to the design and engineering of many aspects of the Janus model line. In this sense then, the new Gryffin 450 is the perfect platform for the rambler.

Design drawing for the 2017 Gryffin 250

It is for good reason that dual sport motorcycles now make up a huge segment of the market with a wide range of capabilities. From the more highway-oriented BMW GS1250 to the trail-ready Suzuki DR650, dual-sport riders are looking for adventure and are more interested in gathering experiences than in looking cool or going fast. This “reisenduro” category of motorcycles, like those old “clubman” models of the twenties, “scramblers” of the sixties, and the recently revived “street scrambler” category of the 2000’s, is a return to the thrilling reason we choose to ramble on these exposed, two-wheeled contraptions.

Janus engineer, Charlie Hansen-Reed, on the prototype Gryffin 450 following the footsteps of Laszlo Peres

As I have argued elsewhere, the technological drive for efficiency, comfort, and safety that has brought us heavier, faster, more comfortable, and feature-laden models is antithetical to the reason we chose to ride motorcycles in the first place. We ride to find a more direct means of interacting with the world around us and for the transformative experience that doing so has on us. We ride for adventure, for the things that happen to us along the way, not merely to arrive at our destination as quickly and comfortably as possible. Lighter weight, reliable motorcycles that invite rider interaction and provide access the greatest adventure are at the heart of what Janus seeks to offer. With the Gryffin 450, Janus now has a model designed squarely for this all-around category that fully embodies our philosophy of “rambling” and “reisenduro”.

The Gryffin 450 prototype in testing winter 2024

Key Takeaways — Scramblers, Reisenduro, and Adventure

• Scramblers started as road bikes modified for off-road fun and endurance. Return of the Cafe Racers

• Reisenduro represents a later evolution — blending touring comfort with genuine off-road capability. Janus Motorcycles

• Dual-sport and adventure bikes grew from this lineage and dominate modern rugged motorcycle use. Janus Motorcycles

• Janus Motorcycles continues this spirit by creating bikes like the Gryffin 450 that honor heritage while embracing simple, joyful exploration.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a scrambler and a dual-sport motorcycle?

A scrambler is typically a road bike modified for light off-road use, while a dual-sport (or Reisenduro) is designed from the ground up to handle both paved and unpaved terrain. Janus Motorcycles

Why is the BMW G/S considered important?

The BMW G/S from the early 1980s is considered one of the first true Reisenduro machines, combining touring comfort with impressive off-road capability. Janus Motorcycles

How does this history relate to Janus Motorcycles?

Modern Janus models like the Gryffin 450 draw inspiration from these dual-purpose roots, offering riders a versatile motorcycle with heritage influence and contemporary engineering. Janus Motorcycles