What is a Scrambler Part One: A History of Specialization

March 20, 2024

Share this post

In 2017 Janus Motorcycles launched the Gryffin 250, a knobby-tired “scrambler” addition to our 250 line which at that time included the more street-oriented Halcyon and Phoenix models. This first iteration of the Gryffin was essentially identical to the since discontinued soft-tail Phoenix model except that it featured the above-mentioned knobby tires and high-routed exhaust system as well as a shorter tank, wide handlebars, an engine guard, and a triple tree mounted front fender. Everything else, including chassis, suspension, running gear, and lighting was (and remains) unchanged. In this similarity to it’s road-going sibling, the more café styled Phoenix, the Gryffin 250 is a faithful heir to the early “scrambler” motorcycle type that first appeared, at least in stock form, in the 1950’s. The earliest factory off-road bikes, ancestors of the modern dirt bike, were just like this – only slightly different twins to a road-going model line.

1920 London to Exeter Run

This early differentiation was the beginning of what over the intervening decades has become an increasing degree of specialization in motorcycles. Gone are the days of throwing some knobby tires on your road machine and riding to a hare scramble event (so too for the most part are the days of driving your competition car to the race track on the weekend). Today we have, not just dedicated on-road versus off-road motorcycles, but a myriad of varieties of each – from trials bikes to motocross machines, hill climbers to rally bikes, enduros, dual-sports, adventure or ADV bikes, and the recently revived “street scrambler” (more on this interesting machine to follow).

Promotional material for the 1920 Auto Cycle Union Six Days Trial

This specialization occurred hand-in-hand with the types of events that catered to motorcycle enthusiasts. The earliest motorcycle competitions were multi-day, long distance “trials” designed to test and improve the industry and provide an entertaining reason to buy and ride (or should we say ramble?). These trials involved a wide range of scoring categories, from durability, braking, speed, fuel consumption, and even sound (the 1920 Auto Cycle Union Six Days Trial awarded marks to the quietest motorcycles). From these early trials, motorcycle and automobile racing diverged into more specialized events like dedicated road racing (the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy), and more extreme off-road events like the International Six Days Trial. Some of the early trials, like the Land’s End Trial (has been held every Easter since 1908), continue to this day.

The complexity of scoring, judging requirements, and time involved in these early trials eventually begged for simplification and further specialization. The machines competing in these early events had almost no specialization. Even the basic conventions of motorcycle design were vague at best in these early days. The one thing that most motorcycles of the era had in common was a certain degree of similarity to the bicycle. Where and in what configuration the engine was placed was still relatively undecided.

A motorcycle that competed on the Isle of Man road race circuit might be identical to one seen tearing up a rutted hill in a trials competition. Perhaps a different way of looking at this would be to say that the difference between what was considered a road and what wasn’t had also not reached the present degree of differentiation. Roads were still designed for travel at the maximum speed of a horse. The kind of paving and surface care we now expect were products of the growing popularity of the motor vehicle and the increased speeds it permitted. Period roads would have born more similarity to a dirt track than our smooth modern highways. Modern dirt bike riders would likely be amazed at the type of motorcycle that was considered appropriate for early off-road events. Early motorcycles of all kinds were ridden in some inspiring locales, especially given the early technology, road conditions, and the lack of repair shops, fuel, and other necessities that we take for granted today.

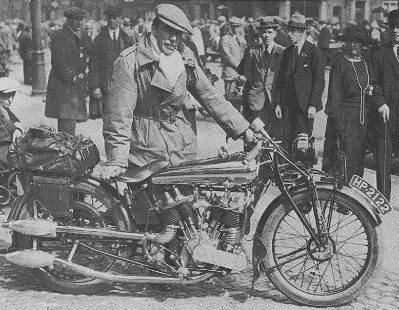

The origins of what we can call true off-road riding find their first recognizable organization in the British “scrambles” of the 1920’s. These scrambles did away with the complex scoring of the competition trials, instead focusing on the minimum time between two points across open country with stream crossings, steep inclines, and plenty of rocks and mud. Starting to sound a bit more familiar? Still, these motorcycles were not much different from those competing in early trials. Riders quickly found low-slung exhausts snagged and dented, large low-profile fenders became caked in mud, and narrow handlebars were difficult to muscle through the demanding terrain. They began to make their own modifications accordingly. By the mid-twenties, manufacturers were supplying “clubman” models with this type of riding in mind. George Brough even fancied the clubman aesthetic and his machines (with their high-mounted exhausts up the side) regularly entered in off-road competitions such as the 1922 A.C.U. Six Days Trial in which George himself raced!

A dapper George Brough in the 1922 A.C.U. Six Days Trial

Through the interwar years, scrambles became increasingly popular in England and on the Continent. Following the Second World War, the scrambler started to take on a more codified form and functional capability, even if it was still not a whole lot more than a modified version of a road-going model. Arguably the first or at least best-known factory scrambler was the 25hp Triumph TR5 Trophy of 1949 which went from winning its debut ISDT to being good at just about all off-road events, be they scrambles or trials, as well as making a great commuter during the work week. By this time other British manufacturers were making more dedicated scramblers as well. BSA, Matchless, AJS, Norton, and Velocette had their own middle-weight models. This size and weight machine was perfect for off-road riding and racing. British and European trials were either in the form of longer multi-hour or multi-day, scored competitions, or relatively short scrambles over closed courses. This type of riding tended to favor smaller, lighter weight machines that could tackle more technical riding. Lightweight enough to manhandle, enough power and torque to handle any terrain, and an approachable easy-to-ride handling that also made them fun on the street. Look at the majority of period scramblers and you will find most fit somewhere in this 250cc to 500cc category.

The 1951 500cc Triumph TR5

Across the pond in the United States a new appeal for off-road riding was growing. California had a very different climate and terrain which fostered a different kind of riding and racing involving longer, higher speed events in the desert with faster, less technical riding. The 500cc Triumphs would become the groundwork for the famous “desert sled”. Lighter and more maneuverable than anything from Harley-Davidson or Indian, the Triumph would become hugely popular in 1950’s America for a reason. On the East Coast, more technical riding developed with enduro and trials events growing in popularity. Yanks like Ohio native, John Penton, had gone from heavy Harley-Davidsons to lighter, smaller British bikes and went on to great success even back on the Continent. Penton went from winning the 1966 Jack Piner Enduro to representing the US seven times in the ISDT. After unsuccessfully trying to convince Husqvarna to build a smaller engined, lighter weight motorcycle, he approached the Austrian brand KTM, who at the time only made bicycles and mopeds. For ten years, these 100cc to 400cc Pentons were incredibly popular in the States until KTM eventually bought out Penton’s operation in 1978. Their US headquarters are still in Ohio.

92-year-old John Penton with the author and prototype Gryffin 250 at the 2018 AMA Vintage Days at Mid-Ohio

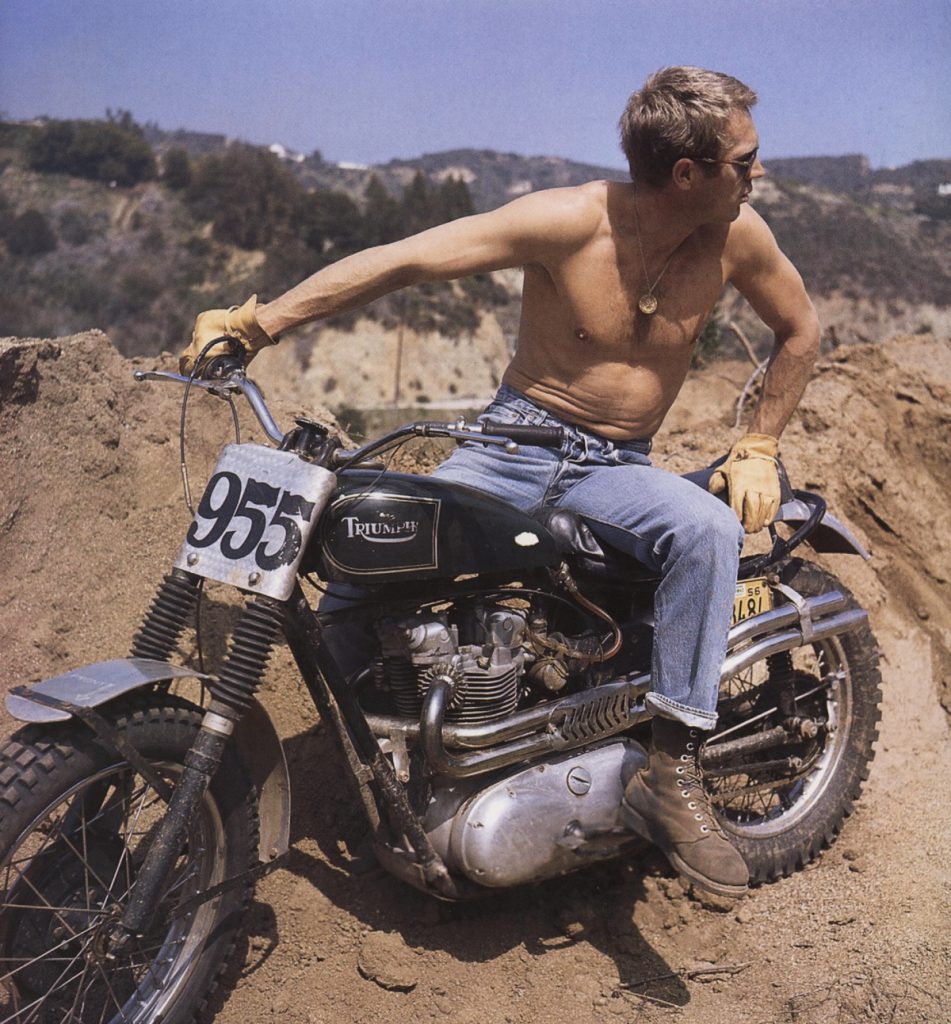

Meanwhile, Californians, charmed by the rugged appeal of celebrities like Steve McQueen and Bud Ekins, and with higher speed desert events like the Big Bear enduro, drove demand for larger machines like the 650cc Triumph TR6. These machines were still lighter than US models and sold well for street use across the US.

McQueen looking cool on a cool machine

Back in Europe, the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme, realizing the growing popularity of scrambling, had created the “European Championship Series” in 1956, an event that would become more and more familiar to the modern day motocross rider. The word Motocross itself is a portmanteau of the French word for motorcycle, motocyclette, and cross country – Motocross. Open country, point-to-point scrambles gave way to circuit-based laps and more and more purpose-built machines.

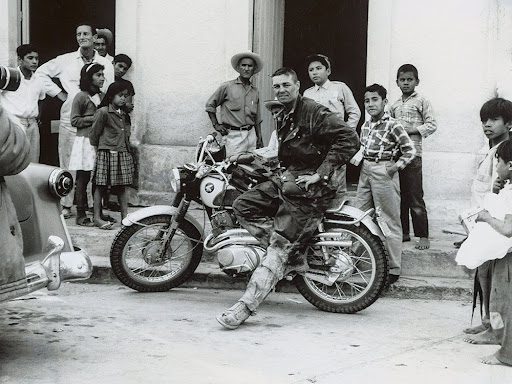

Dave Ekins with his Baja-tested Honda CL77

Then in 1962, Honda hired Bud Ekins brother Dave (an accomplished ISDT racer) to ride their new CL77 from Tijuana to La Paz in Baja. The new CL77 was their scrambler version of the 305cc CB77 Super Hawk. Not only did they inspire the Baja 1000 enduro race, but cemented the success of Honda’s incredibly popular CL scrambler line. Honda went on to offer the scrambler CL version of their CB models in everything from 125cc to 400cc with the CL350 winning the Baja 1000 in 1971.

There are too many wonderful scramblers from these years to mention: Italians Ducatis, Parillas and even MV Agustas; Japanese models from the Yamaha, Suzuki, and Kawasaki; Spanish Bultacos, OSSAs, Montessas; Germans Sachs; British Greeves and Dots (with leading-link forks), and many more.

The stunning 1968 MV Agusta 250B (bicylindrica)

By the 1970s the level of specialization in motorcycles had outstripped what the scrambler–that slightly more rugged sibling of the road going model–could accommodate. Advances in suspension geometry like the mono-shock rear suspension which allowed for radically increased suspension travel (and aerial acrobatics), more powerful and lighter two stroke power plants, and more specialized and demanding events made the twin-shocked good-at-everything scrambler increasingly obsolete for serious off-road competition. For more on the story of the the technological advances and specialization in rear suspension, see part 2 of our post on the Halcyon 450 rear suspension: .

In part two of this post we will look at the advent of the adventure or ADV bike and the timely return of the scrambler.