Bulletproof: The Heritage of the Janus 250 Motorcycle Engine

October 22, 2019

Share this post

We get a lot of questions about our engines. Why so small? Why not made in the US? Why air-cooled? Why carbureted? It all started with a 50cc motorcycle… read on!

The Paragon, Devin, and my first motorcycle build from scratch: an 80cc homage to 1960s small-displacement grand prix motorcycling.

Let’s start off with the question of small displacement. Just about everything we do at Janus is based on our personal riding experience. We come from a background of small-displacement engines and lightweight bikes. For instance, Devin and I started off our love for two wheels on vintage mopeds—that’s right, the ungainly little two strokes with pedals. Right away, we realized that some of the most fun that can be had and the majority of riding that we encountered happened in our daily activities: riding to work, riding with friends to lunch, riding to our favorite nearby town for a beer or a burrito. All those things were more fun on two wheels and even more fun when you were fully aware of the machine that was taking you there. They are also more fun when you can take advantage of the full potential of the machine. Shifting through all the gears, accelerating at full throttle and enjoying the whole process of piloting and even maintaining a simple, accessible machine—a machine that has fewer moving parts than a sewing machine and can be essentially taken apart and rebuilt with the tools in your saddlebag. There is a lot of fun to be had on a powerful sport bike, cruising motorcycle, or dual sport, but for us, those kinds of experiences often sideline the real point of riding: to feel the wind in your face, to enjoy the journey, and to be a part of the passing scenery.

So when it came to selecting the right engine for Janus Motorcycles, we sought something with enough power to hit the highway for short stints (because that’s something we all have to do at some point) and to accelerate from a stoplight with a grin on your face. At the same time, we knew that we also wanted an engine that we and our customers could take full advantage of—not on the track, not with traffic enforcement hot on our trail, and not with a string of expensive repairs and maintenance. For a number of reasons, we were also looking for an engine that could be maintained using the tools in most people’s garage. What we wanted was the simplest, most reliable motorcycle engine in the world.

The bulletproof air-cooled, carbureted Janus 250 engine, seen here in the Halcyon 250.

Why air-cooled?

A customer’s image of their Halcyon 50cc motorcycle with water-cooled 2-stroke and radiator. Image courtesy Daniel Shewmaker.

Louise Thaden Field (VBT)

Bentonville AR USA

Our first model, the Halcyon 50 was a liquid-cooled 2-stroke 50cc motorcycle. While it was a great little engine, it did have a surprising level of complexity. Radiator, water pump, thermostat, and all the necessary hoses, etc. all contributed to a bike that just wasn’t as simple or easy to maintain as it could be. Because of increased emissions regulations over the past 40 years and the never-ending quest for more horsepower, most manufacturers either already use or are headed in the direction of liquid cooling and fuel injection. This technology reduces emissions, makes calibration (with the right equipment) relatively quick, and dramatically increases performance. However, a small engine is by its very nature highly fuel-efficient and clean-burning. For instance, our 250 engine was extremely close to passing EPA exhaust emissions testing without even having an exhaust catalyst in place. Our goal for a simple, appropriately powered engine did not require the additional horsepower that water cooling allows, and the simple, traditional aesthetics of the air-cooling fins was a perfect fit for our traditional model line. Add to that the simplicity of eliminating the radiator, water pump, and all the hoses that go along with liquid cooling, and it made perfect sense to go with an air-cooled engine.

Why carbureted?

To continue that simplicity, it was an easy choice to use a traditional carburetor rather than fuel injection. Again, the main reason for the move to fuel injection over the past 20 years has been to control emissions. With a clean-burning engine, this wasn’t as much of an issue for us.

Another reason for the move away from carburetors is that carbureted engines require more operator involvement. That means that they require the application of the choke when starting on colder days, and usually need to be warmed up before riding and cleaned every so often. But they have no electrical requirements, no computer chips, and they can be rebuilt with regular shop tools. While this may present a hurdle for Honda or other mass-production brands, our mission is to create a machine that DOES require operator involvement. We want our customers to be able to warm up the engine, to feel the RPMs change as the metal and oil increase in temperature, and to have switches to flip, gauges to read, and levers to shift!

Detail of the Janus 250 engine.

If there is a modern vehicle on the opposite end of the spectrum from autonomous vehicles and artificial intelligence, a Janus would have to be near the top of the list. The founders of the earliest motorcycle brands would be almost as familiar with the Janus motor as with their early designs. Of course, technology has come a long way since the early days of the internal combustion engine and our engines take full advantage of recent advances in metallurgy, oils, machining tolerances, transmissions, and power output, but the spirit of the internal combustion engine lives on in a Janus, right down to the kick starter. If using the choke on a cold morning isn’t something that would interest you, then we might recommend something a bit less involved—perhaps a Prius?

Why not made in the US?

While this all seems like a tall order in the current market of high-powered, high-tech engines, we started by looking at engines made in places where regular maintenance is harder to find and where reliability is prized above state-of-the-art technology. Our reasoning was that if these types of engines could operate under the stress of constant use, not just for leisure, but for everyday primary transport, then they would probably do a fantastic job under the typical kind of riding that our motorcycles were destined for here in the United States. They would also provide the same time-tested traditional function and aesthetics as our classical designs. Add to that the complete absence of US manufacturers of small-displacement motorcycle engines and we had to start by looking further afield.

The CG250: a traditional and reliable engine

This brings us to one of the most significant but least known engines in the world: the CG250. In the early 1970s Honda was in its heyday. The CB series of motorcycles were some of the best two-wheeled vehicles available anywhere for performance, reliability, and fun. But Honda had a problem. All across the third world, their small CB series bikes were experiencing issues. They just weren’t designed for the kind of everyday abuse that was being handed to them. They weren’t designed to haul 75 ducks, or two goats, or a family of ten.

So around this time, Honda decided to make the most bulletproof engine they could imagine. Two of their lead designers, Takeshi Inagaki and Einosuke Miyachi spent a month visiting Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Iran, and Pakistan observing the way motorcycles were used. What they witnessed was far worse than they had imagined. What little repair there wasn’t performed until the motorcycles literally couldn’t run anymore. Oil was used until it turned to sludge, and when the repair was necessary it meant rebuilding the entire motorcycle. By the time the two headed back to Japan, they knew that Honda needed a very special new engine.

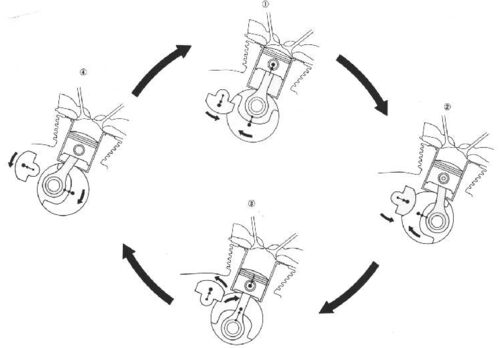

The new engine would be a 125cc version of their single-cylinder CB125, but it would dispense with the overhead camshafts in favor of a much simpler overhead valve design that used a unique rocker arrangement that allowed both exhaust and intake valves to be operated by a single cam. The cam was operated by a gear right off the crankshaft and low in the engine to provide constant lubrication. It pushed short, robust rods that operated the valves in the cylinder head. No more cams, cam bearings, cam chains, or tensioners meant less need for lubrication and a design that had far, far fewer moving parts. The overhead cam CB125 may have produced more power, but it was extremely sensitive to lack of oil, the wrong oil, or dirt, etc.

Honda commenced production of the new engine in Japan, but since the model was specifically designed for developing markets, the goal from the beginning was to have production move to satellite factories in the target regions. Most of the components were therefore outsourced to Brazil, China, Taiwan, and Pakistan, where they are still in production. In the 30+ years, it has been in production, it has become one of, if not the most produced motorcycle engines in the world.

By the mid-1990s, with increased maintenance and support in developing markets, Honda started focusing on higher performance engines with more technologically advanced features. While production of the CG continues to this day, numerous suppliers around this time began manufacturing variations of the now outdated engine. The most significant variation among these new manufacturers was the transformation of the engine from 125cc to a 229cc. Since the engine was so robust and put out relatively little horsepower, this increase in displacement was easily accomplished with no effect on reliability. The one side effect of the increase in displacement was an increase in the vibration of the single-cylinder engine. While there continue to be versions of the 250 design being made without it, several manufacturers decided to add a balance shaft to the engine. A balance shaft is a component used on many single-cylinder engines to provide a counterweight to the motion of the piston. This serves to cancel out the often excessive vibrations of a single-cylinder “thumper” engine.

When we first started prototyping and testing engines for our 250 model line, we purchased several CG250 engine variants and tested them over the first year of development. The first engine we tested in our prototypes suffered from a clunky transmission and excessive vibrations. We quickly realized that we needed to keep looking for a better quality engine manufacturer if we wanted the high standard of quality that we were used to from old Honda CB’s we had owned and restored. We ended up locating a manufacturer of the CG250 that not only had a US import location but were also willing to build engines for us in the small quantities that we could afford.

Emissions tech, Matt, onboard the Janus test mule at S&S Cycle’s test facility in Lacrosse, Wisconsin.

We were immediately struck, not only with the smooth shifting and good performance of the engine but with the quality and overall appearance. From the case castings to the gear machining, these were engines that could compare to any Honda CB that we had encountered. While they were nowhere near as cheap as the previous engine variants we had tested, we knew after months of testing and inspection that we had found an engine with the quality and performance that would fit our motorcycles. Not only that, but we had a relationship with the manufacturer and could order any part of the engine. The next trial of the engine would be to see if it would pass EPA emissions testing.

The EPA motorcycle certification process not only requires that every motorcycle engine family meet their stringent exhaust emissions standards, but that they do so for the full lifespan of the engine. This meant that our test bike had to simulate the required 18,000-kilometer duration testing, but also stay within EPA emissions limits. With a year of preliminary testing and calibration, working internally with our “engineer emeritus”, Ken Miller, and with S & S Cycle of Viola, Wisconsin, we were able to pass the testing with flying colors. This was a double victory for us. We had opened up the ability to sell our motorcycles in all 50 states as well as proved the quality of the engine. Poor emissions are the telltale sign of engine wear or malfunction. That the engine operated smoothly throughout the testing is a witness, not only to its clean-burning emissions but to its overall durability.

To date, with over 250 Janus motorcycles on the road, we have yet to experience any issues with our engines. We have had our share of issues with the occasional electrical, fuel delivery, or other odd manufacturing defects, but for better or worse, these have all been the product of the parts and processes we build right here in Goshen, Indiana, not with the engine that is built half a world away! We could not be happier with our engine and are working hard to let everyone in on the secret of the CG250 and the fun of small-displacement motorcycling.

Yours truly taking the test bike out for another set of runs in the frigid northern Indiana winter.

To that end, we have completed several endurance runs in an effort to both test the bikes and prove their reliability. This spring, I piloted Halcyon #68 from San Francisco to New York City in six days riding with a bunch of Honda Goldwings and BMW GS adventure bikes, the smallest of which, at 1,200cc’s, was almost five times the displacement of the Janus! I averaged 650 miles a day on interstate 80 to earn an Iron Butt Certification (see my blog posts detailing that ride). The bike performed flawlessly for the entire ride, although I was a bit sore for a week or two afterward. This fall, my friend Jesse and I completed a Saddle Sore 1000 by riding Halcyons 1,000 miles around Lake Michigan in under 24 hours. We weren’t fast (we got in with just 30 minutes to spare), but we made it in fine form and once again, without a single engine issue.

We have moved on from our 50cc motorcycle and moped days, but we are fascinated by the rich history of these remarkable engines and continue to search out ways to put them through their paces. We encourage you to come out and try one of our motorcycles if you have any doubts. We think you’ll be pleasantly surprised, just like most of our Discovery Day attendees and owners, with the smooth-shifting, quick acceleration, and easy power of our traditional, air-cooled, carbureted, engine.

Official Janus Gear can only be found in our Shop.

Looking for more about us? Read on here!

Follow us on Facebook And Instagram.

https://janusmotorcycles.com/product/indiana-janus-flag-tee/