The Halcyon 450 Rear Suspension Design and History Part Two

October 29, 2021

Share this post

The Halcyon 450 Rear Suspension Design and History Part Two

This is the second of a two-part discussion of the Halcyon 450’s rear suspension design and history. To catch up on part one, click here!

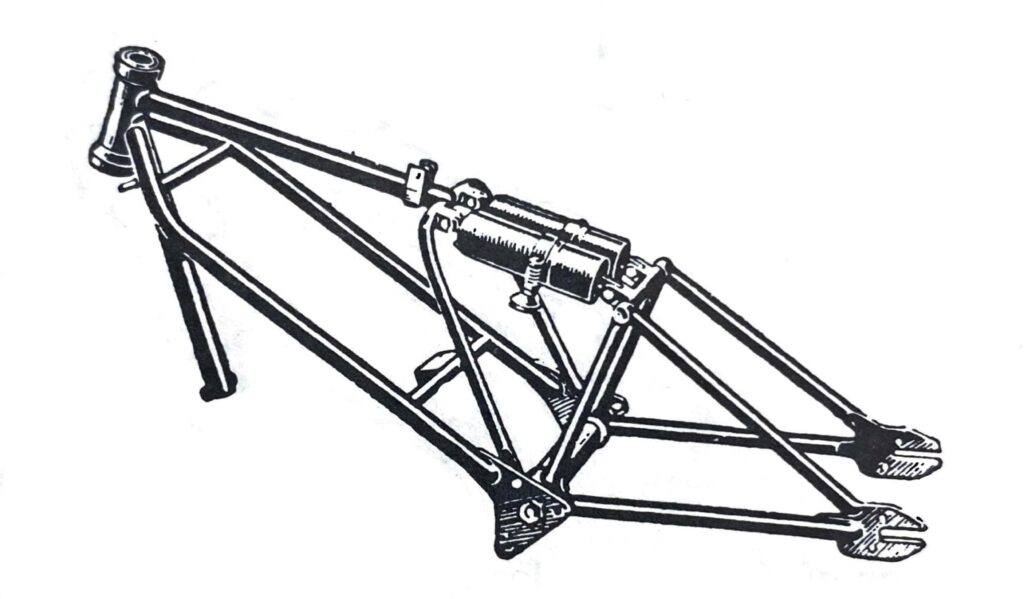

As early as the 1950’s, developments in racing would lead to a variety of triangulated rear suspension designs using one or two shock absorbers, including Doug Hele’s 1952 BSA 250cc GP racer (note the leading link front fork). But it would be the growing interest and development of off-road motorcycles that would push the next evolution in rear suspension technology.

Tilkens and the Monoshock

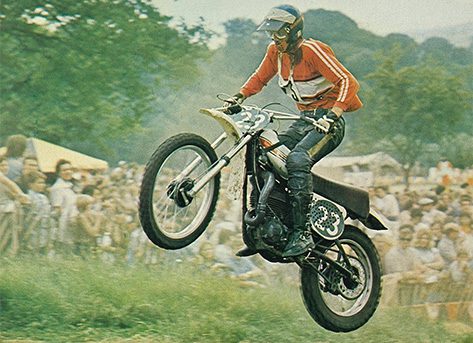

Starting in the late 60’s Belgian engineering teacher, Lucien Tilkens, known at the time for his sugar beat harvesting equipment, began experimenting with a new rear suspension design capable of handling the high power of his son’s friend (and later Suzuki works motocross racer) Sylvain Geboers’ powerful, but poor handling CZ 400. Though powerful, Tilken’s theory was that the lack of rigidity was the cause of the machine’s difficult handling, not its increased power. His answer was to triangulate the rear swing arm and connect it straight to the steering head with a long gas shock borrowed from a Citroën car. What he came up with was not only a more rigid chassis design (much like that of the earlier Vincent), but even more significantly, the accidental benefit of the drastically increased suspension travel.

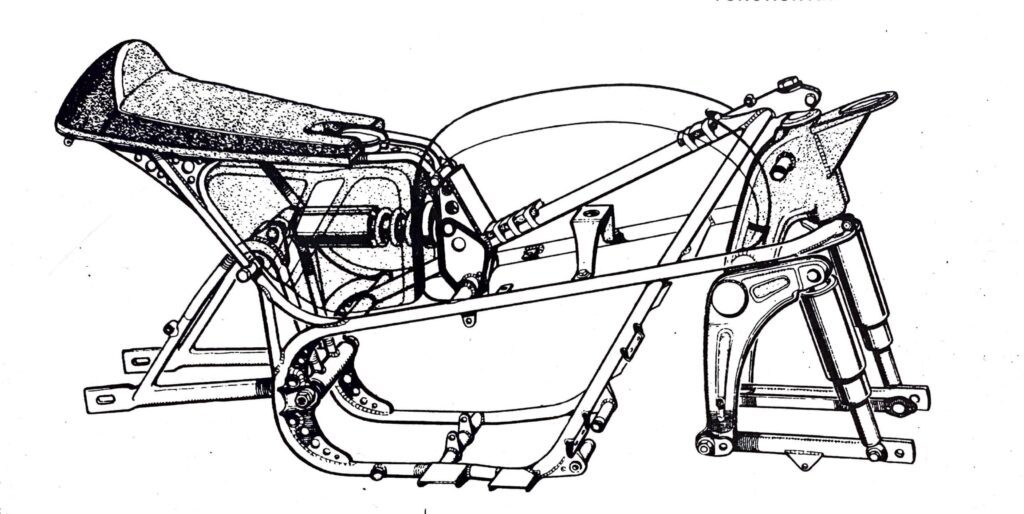

At this time, rear suspension travel on grand prize motocross bikes maxed out around four inches. Tilkens’ design, however, allowed for almost double that travel with the possibility of even more. Interestingly, Tilkens didn’t realize the significance of this, and because he was unable to explain how his design performed better, both Honda and Suzuki turned down his offer to sell them the design. It would be Yamaha who would eventually decide to purchase the design in 1972. The next year they campaigned it in the 1973 season, famously winning the 250cc Motocross World Championship with Hakan Andersson at the helm. What took everyone, including the riders and designers, time to figure out was that it was not merely the increased stiffness of the frame, but the long travel suspension that allowed the bike to go faster in the demanding motocross terrain. Within a matter of months, every major motocross maker was frantically figuring out how to increase rear suspension travel and stay competitive. In 1975 Yamaha launched the YZ250, the first production motocross bike with a monoshock suspension. Over the next 5 years, all major manufacturer had shifted to variations of the monoshock design and suspension travel had increased to almost a foot.

Linkage Designs

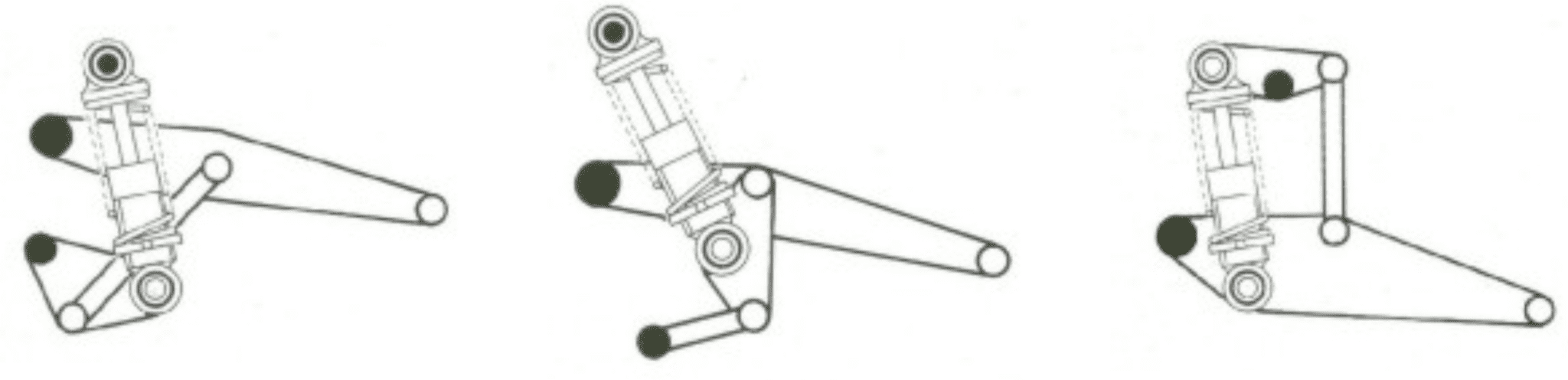

In addition to the increased travel that the monoshock rear suspension allowed, designers realized that through the use of a system of linkages between the shock absorber and the swing arm, they were able to add highly tunable rates to the spring and damping to provide even better handling. Reductions in unsprung weight, advances in frame design, along with improved manufacturing processes, meant that the monoshock design had advantages for road bikes as well. Over the next decade, the entire motorcycle industry, including almost all sport and touring motorcycles, shifted to a monoshock rear suspension. That improved suspension travel along with variable suspension rates were the main reason for the predominance of the monoshock design, and not merely rigidity, as posited by Tilkens, is born out by the fact that most designs returned to variations on the simple, un-triangulated, two-legged pivoted fork, or in the modified single-sided form, albeit with considerably improvements in metallurgy and advances in manufacturing processes.

While manufacturers in the late 70s and early 80s scrambled to come up with their own versions of the monoshock linkage system, each with their own trademarked name, the basic principles remained essentially the same and allowed for a wide selection of suspension rates by changing the lengths and proportions of the various components. Another benefit of the linkage design was that the various components, including the much smaller shock absorber, could be placed almost anywhere, so long as the proportions and rigidity were retained.

A Return To Direct Suspension

Motorcycles are an interesting pairing of state-of-the-art technology and a conservative desire to stick with what is known and understood. Over the last 20 years, some leading brands have decided to ditch the linkage system in favor of the simplicity of a direct shock connecting the swing arm to the frame. KTM, a leader in the off-road market, introduced their “PDS” or Progressive Damping System, on their 1997 “Jackpiner” which did away with the linkage entirely by using a progressive rate shock absorber. While the debate over PDS vs. linkage systems continues, one system does not appear to have an overall advantage, except that the direct system is less complicated, weighs less, and has better ground clearance.

Aesthetics

While track performance provided the primary reason for development of the first linkage rear suspension designs, other manufacturers chose cantilever monoshock designs for purely aesthetic reasons, as was the case with Harley Davidson’s FXST Softail which sought to mimic the look of a hardtail motorcycle. Triumph’s recently introduced “Bobber” uses a triangulated swing arm and cantilever shock for similar aesthetic reasons. Both these designs feature frame rails that appear to run from the steering head all the way back to the rear axle as found on early hardtail motorcycles.

Our choice of design

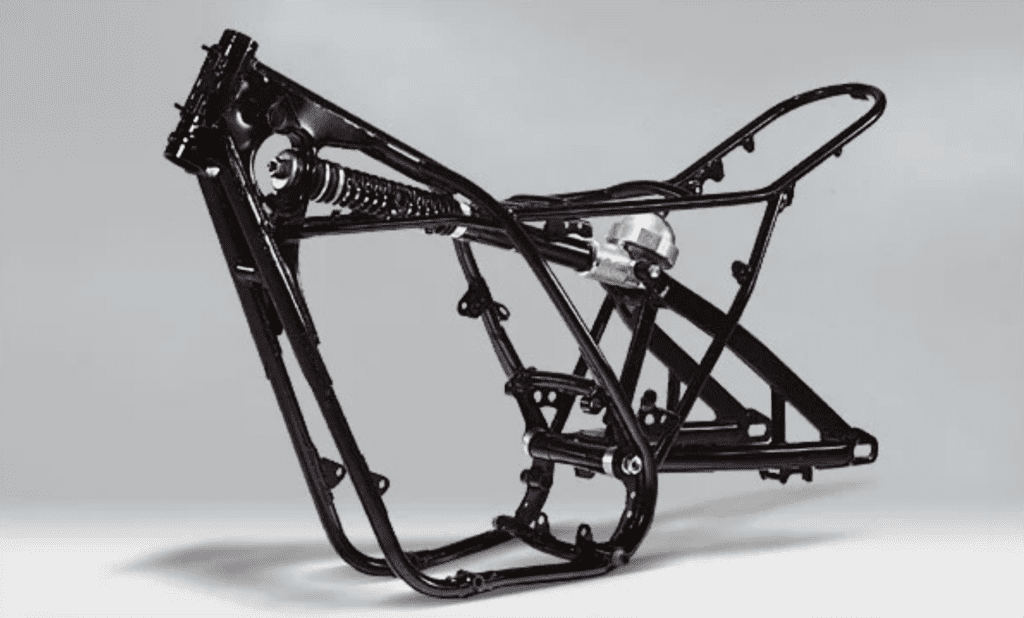

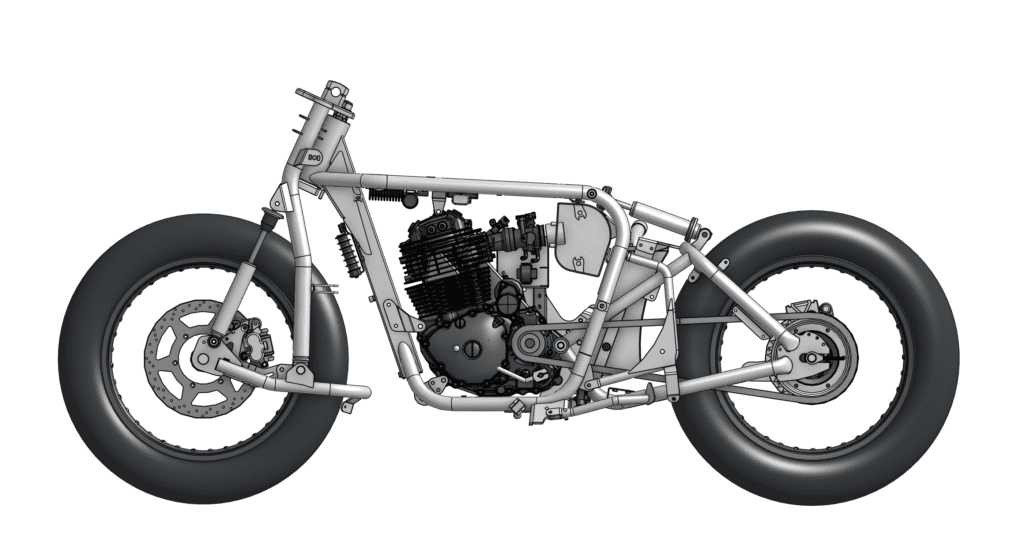

As we began the schematic design of the Halcyon 450 model, we knew from the start that the clean, minimal lines of the existing hardtail Halcyon line was a significant part of the overall appeal of the design. For this reason, traditional twin vertical shocks were never really considered. Instead, we began by looking at the modern linkage monoshock system with the suspension unit located vertically ahead of the rear wheel.

After running a number of simulations using alternative suspension expert, Tony Foal’s, analysis software and our own CAD models, we realized that the benefits of such a system were in many cases outweighed by its inherent complexity. One of the downsides of the linkage system is that suspension stresses on the chassis are concentrated by the mechanical advantage of the linkage system and can be many times higher than those experienced with a simple direct suspension system. While this presents less of an issue for modern chassis designed around a linkage system, it meant that such a system would not be easily adapted to our double cradle “featherbed” style main frame. In addition, each one of those highly loaded linkages would require complex, high tolerance bearings and regular maintenance as opposed to the simple, bolted connection of a direct suspension system.

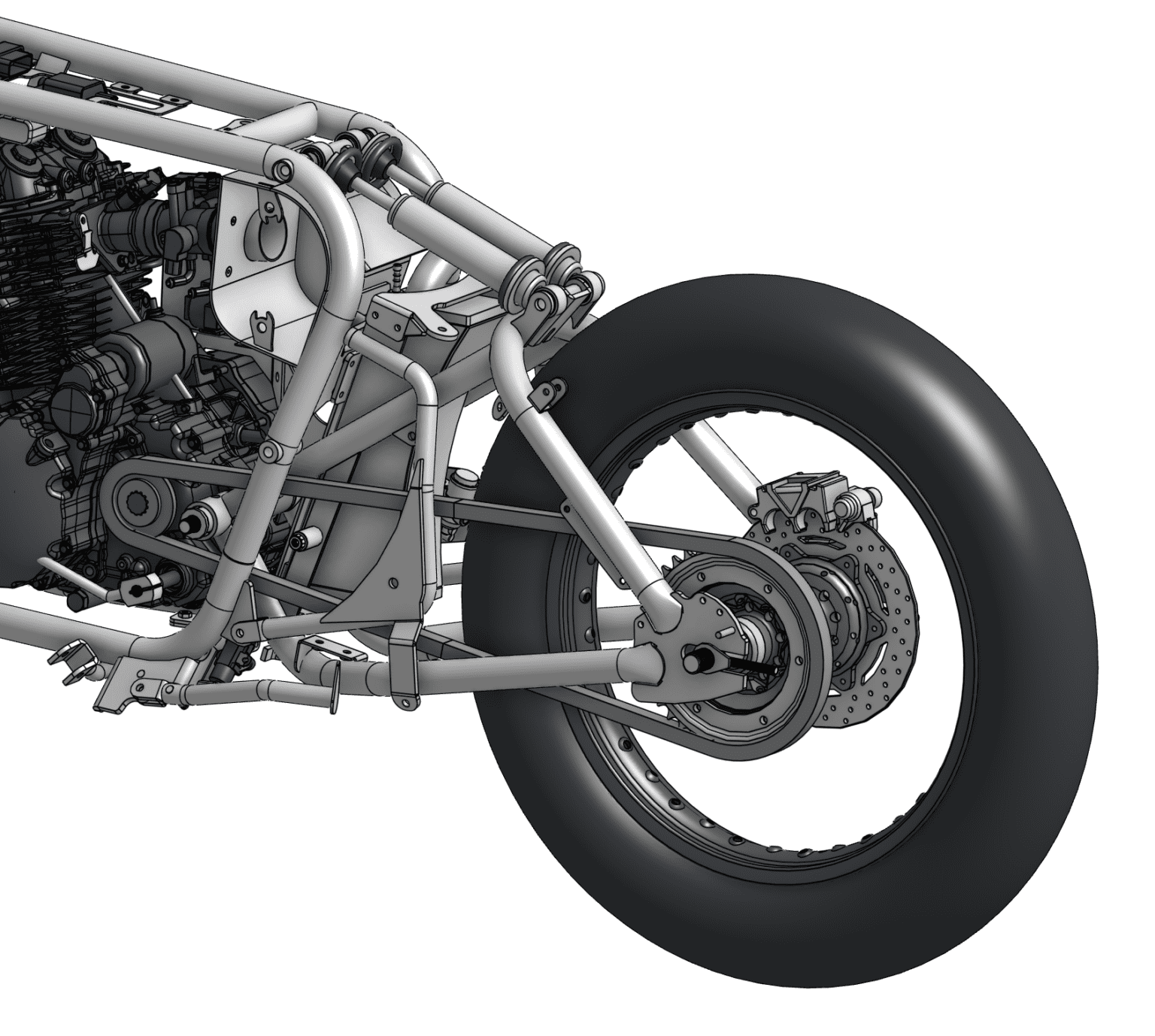

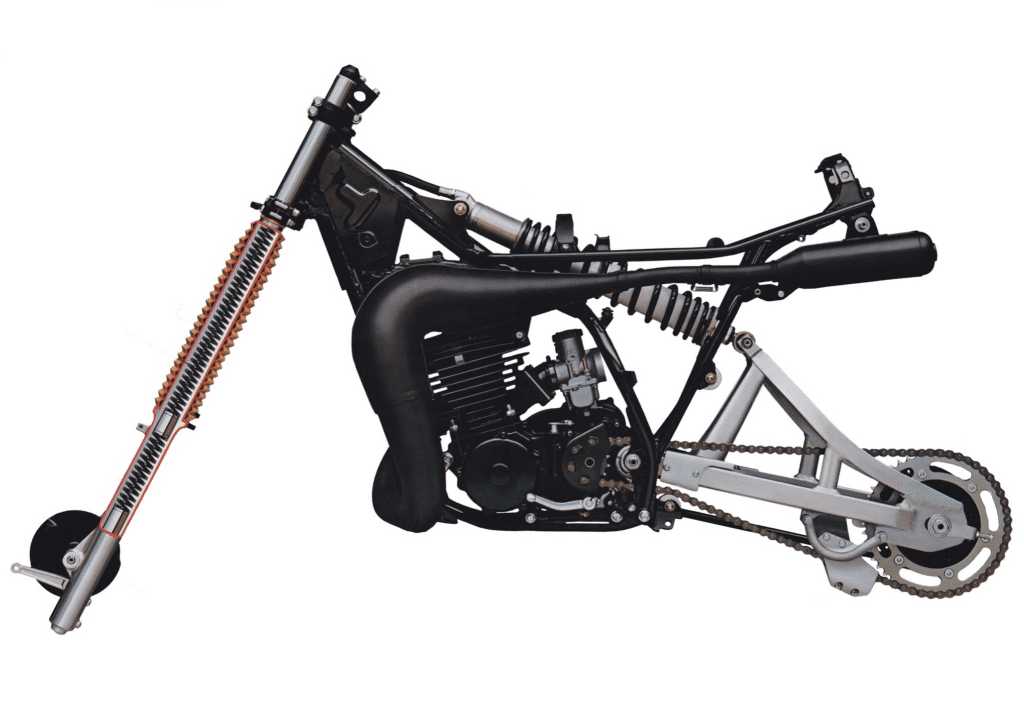

These considerations, paired with the layout of our double-cradle frame, resulted in a change of direction to something that looked surprisingly similar to Phil Vincent’s 100 year-old design. This layout had several points in its favor. By locating the suspension unit between the top of the triangulated swing arm and the top corner of the rear of the main frame, a number of benefits could be realized:

- The clean, traditional lines of the hardtail could be fully maintained

- The suspension stresses acting on the frame could be significantly reduced down to something similar to the twin shocks we were used to from the 250 softail line

- The suspension unit could be run directly from the top of the triangulated swing arm to the upper rear corner of the frame, obviating the need for any complex linkages and bearings

- And finally, that top shock mount landed right where the seat pivot needed to be, as well as at a convenient location for mounting a passenger seat or subframe for future models.

Another factor that contributed to the move away from a linkage system was the fact that we could achieve similar progressive suspension rates with progressive spring windings just like already in use on our 250 line.

The Halcyon 450 continues the clean lines of its predecessors, the Halcyon 50 and 250, while its cantilever swing arm and paired shocks offer a comfortable ride with all the road-holding performance of traditional vertical twin shocks, with the additional rigidity offered by the triangulation both vertically and laterally. Progressively wound springs provide good spring rate with fully adjustable preload via threaded lock nuts. The end result has been a functional design that builds on the character and beauty of the original Halcyon concept, but adds increased comfort, contemporary road-holding ability, and the rigidity to handle the increased power and weight of the newest addition to the Janus model line.

We hope you have enjoyed this look at the design and history of the Halcyon 450’s rear suspension. To learn more about the frame and forks designs, both similarly rooted in the history of motorcycle history, check out our Youtube channel and parts talks.