The Halcyon 450 Rear Suspension Design and History Part One

September 21, 2021

Share this post

The Halcyon 450 Rear Suspension Design and History Part One

This is the first of a two-part discussion of the Halcyon 450’s rear suspension design and history. To catch part two, click here!

While the new Halcyon 450 shares much in common with its predecessors, the Halcyon 50 and 250, perhaps one of the most significant differences to the design is the addition of rear suspension. While the 250 can get away without rear suspension, in large part due to its low weight, top speed, and intended use, the larger and faster Halcyon 450 made rear suspension a requirement.

However, rather than going with the simple and ubiquitous rear fork with paired shocks that we use on the Phoenix and Gryffin 250 models, we wanted to preserve the clean, minimal lines of the previous hardtail Halcyon models. A look at the history of motorcycles will present almost as many solutions to the problem of smoothing road irregularities as there have been brands.

Before we embark on a look at the history of rear suspension and our reasons for selecting one design over another, let’s take a look at the two main functions of rear suspension, or indeed suspension in general. Vehicle suspension goes back at least to the royal carriages of the late fourteenth century when the carriage itself was literally “suspended” from the chassis by leather straps and would swing back and forth instead of being jolted by the irregularities of the road. The primary purpose of the suspension in these early examples was to isolate the occupants from the discomfort of the worst bumps and jolts of the road.

Images credit, Carriages by Jacques Damase.

Even with the standardization of steel springs in carriages during the second half of the eighteenth century, there was little benefit to the speed or road holding ability of the carriage other than the increased comfort and endurance they afforded. However, with the advent of the internal combustion engine and newly possible speeds in excess of that of a horse, the ability of the wheel to stay in contact with the road became increasingly important. And so we begin to see racing car and motorcycle designs which replace the comfort of the operator with the road-hold performance of the machine as the primary reason for suspension. Modern production suspension designs must of course accomplish both these important functions.

The first widely produced motorcycle frames were essentially identical to the bicycle frames of the period with the addition of an engine bolted wherever there was room. Much like those bicycle frames were, and still continue to this day, these early motorcycles rigidly mounted the rear wheel to the main frame, just as on the Janus Halcyon 50 and 250 model lines. This typically took the form of a pair of tubes triangulated off the seat post which supported the rear axle. Just as on their less complicated predecessors, motorcycles began as bent steel tube, brazed together with special lugs at the points of connection.

Although there were many early attempts to introduce suspension to the rear of the bike, including springs and even air suspension (ASL Motorcycles of the early teens), the endeavor was largely abandoned for another forty years, with several notable exceptions. The reasons for this lack of interest in rear suspension on the part of most manufacturers are debatable, but the relative lightweight, as well as lower power and speed of period machines, reduced the need for full suspension, so long as rider comfort was addressed with a well-sprung seat. That the lack of suitable damping technology at the time resulted in rear suspension designs which were hardly more comfortable (or better performing) than a sprung seat meant that customers simply didn’t want rear suspension enough to justify the higher cost.

Previous

Next

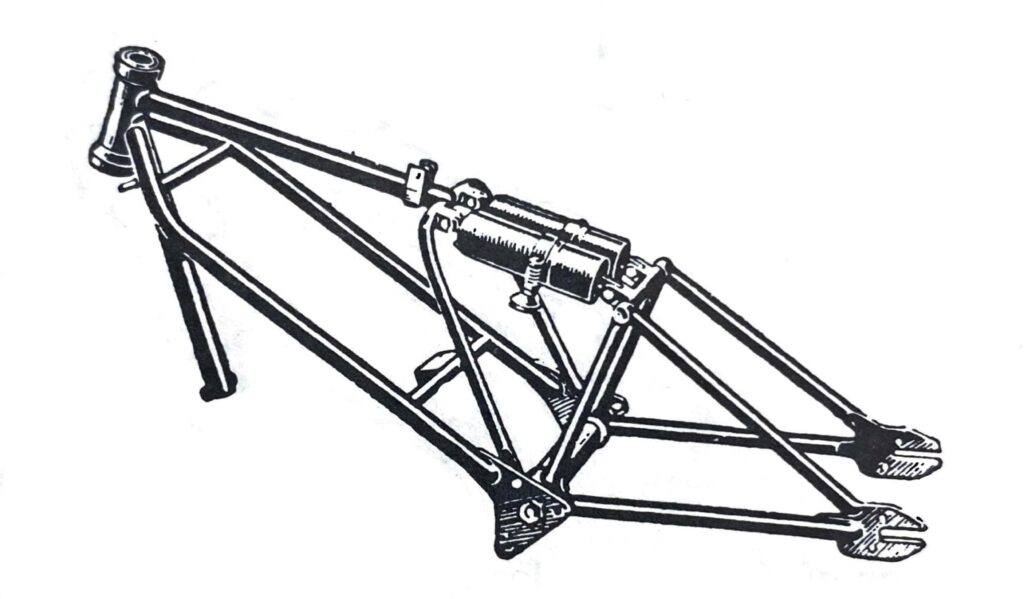

More expensive brands such as Vincent HRD and Brough Superior, less concerned with the cost of their state-of-the-art machines, introduced more advanced rear suspension designs as early as the late twenties. Phil Vincent’s triangulated cantilever rear suspension appeared on the first Vincent HRD models in 1928 and was further developed throughout Vincent production, while Brough Superior went with the Bentley and Draper system that was more easily retrofitted to their existing hardtail frame geometry.

By the mid-to-late thirties, more manufacturers were moving towards rear suspension. The easiest way to accomplish this with minimal modifications to existing frame designs was to add plunger-type rear suspension. This design added spring boxes to each side of the rear axle which could then slide up and down in the rigid rear transom of the still essentially hardtail frame. Both Norton and BMW were able to achieve racing successes with this design and did much to win popular acceptance for the rear suspension concept, however the plunger design suffered from many disadvantages. Because the two plungers were connected by nothing more than the relatively flexible axle, lateral loading of the wheel, such as that experienced when encountering bumps while cornering, could result in the wheel leaving the vertical plane, similarly to what can occur with telescopic front forks. Additionally, the use of the spring boxes at the rear axle did away with the natural triangulation of the old hardtail rear transom and contributed to further loss of rigidity.

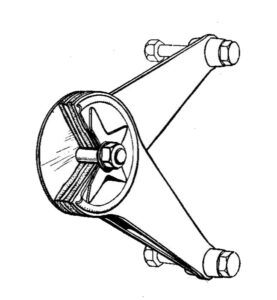

Another problem with plunger suspension is that, as the rear axle travels up or down, the drive chain becomes progressively tighter, meaning that its travel is severely limited and that the chain must be left at its most slack in the position where it is used most. This was a problem that the Vincent cantilever design did away with by placing the suspension pivot about a point, if not the exact same, then very close to the drive chain counter sprocket. Because of the increased length of this swinging arm and the proximity of the pivot to the counter sprocket, minimal changes in chain tension were possible and the geometry could be designed such that the chain would get looser at the extremes of suspension travel. By the late thirties, Moto Guzzi and Velocette had moved to a similar swinging arm with a pivot near the counter sprocket. Moto Guzzi triangulated the swinging arm below the fork using a tension spring below the engine with friction damping (a design Buell fans might be surprised to see). But it would be Velocette who would have the distinction of being the first to use damped shock absorbers as we know them, first on their works racers of the mid-thirties, and then on the production Mark VIII KTT in 1939.

Velocette chose to do away with the triangulation of the rear swinging arm, instead using a now familiar two-legged, pivoted plain fork with twin damped oil/gas shock absorbers (technology borrowed directly from aviation landing gear), one on each side in the arrangement that would become almost universal for many years and can still be found on more traditional designs such as the Triumph Bonneville line and the Janus Gryffin and Phoenix 250.

Prior to this hydraulic shock absorber, damping was accomplished primarily through friction. Vincent and Brough’s initial designs used friction dampers, as did most available front suspension systems. Oil or gas damping provided dramatic improvements in handling and comfort and doubtless was a significant factor in the industry’s move toward full suspension becoming standard kit on almost all machines in the post-war era.

While Velocette can claim primacy to the use of damped shock absorbers in their conventional paired configuration, it was not until Irishman Rex McCandless’s revolutionary “featherbed” frame, built for the 1950 Isle of Man TT, that the paired coil over shock mated to the plain, two-legged pivoted fork would be accepted as the industry standard. For more on the featherbed frame and our decision to use it on our 50 and 250 line, check out our Parts Talk video on frames.

Over the following four decades the plain pivoted fork with twin coil over shocks would come to reign supreme as the rear suspension design of choice for almost all manufacturers. The simple design was easy to manufacture and worked well in most conditions. In either case, it was a substantial evolution from pre-war motorcycles with nothing more than their sprung seats and it would allow motorcycles to pack more power and go faster than ever before. Ironically, Velocette’s aviation-inspired suspension was to be superseded by the requirements of a new type of motorcycle as at home in the air as in the dirt.

In part two we will look at the revolution in motorcycle design brought about by motocross long-travel monoshock suspension, it’s benefits, and why we chose not to use it and instead go back to the Vincent cantilever-type swing arm on the Halcyon 450.

This article reflects the production configuration at the time it was written. As part of our ongoing refinement process, certain components or specifications may evolve over time.